Prevalence and distribution

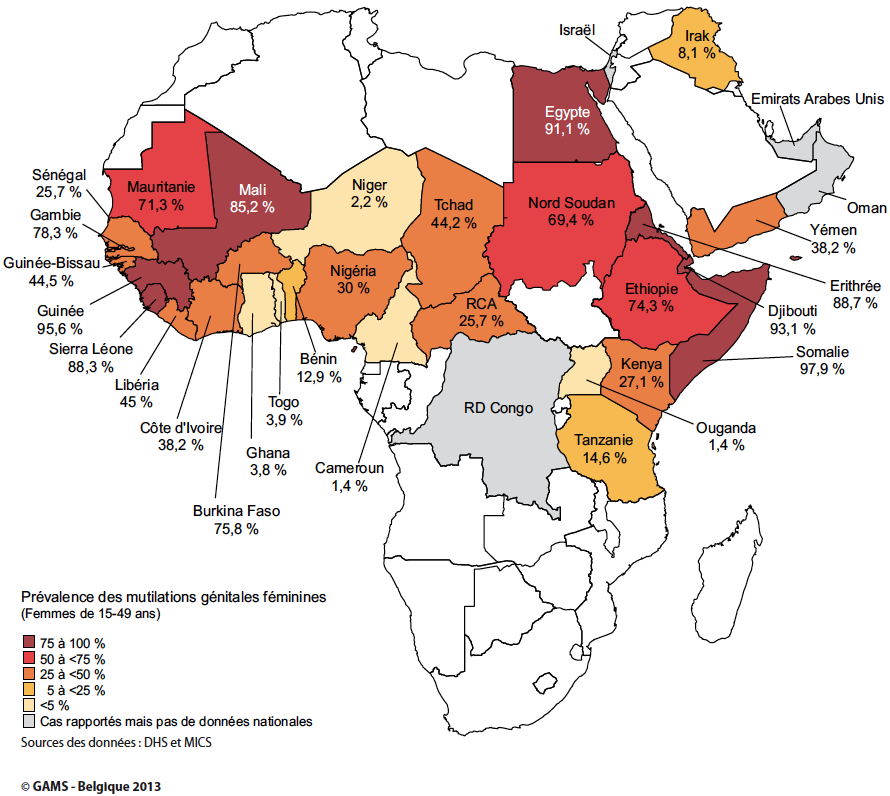

Although no complete figures are available for some of the countries concerned, sexual mutilation is reportedly practised in 33 countries, 28 of which sub-Saharan, and several on the Arabic peninsula as well as in Asia (Indonesia). As indicated below, the frequence of FGM varies greatly from country to country: up to 99% in Somalia, but less than 5% in Uganda. The distribution varies depending on region and social group.

- Excision (cutting) is practised mainly in West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, northern Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo and Chad), but also in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

- Infibulation is practised in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia), Egypt, Sudan and in the southern part of the Arabic peninsula. In a number of countries (Egypt, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal) both occur.

In Europe, emigrants from the impacted countries uphold the practice by calling upon a local cutter or by sending their daughters to the country of origin to undergo FGM. Therefore it is important that health and child-care professionals are well aware of the problem and do their share of prevention.

Why FGM is practised

According to the World Health Organization (2008), ‘the causes of female genital mutilation include a mix of cultural, religious and social factors within families and communities’. The communities involved bring up various reasons for performing excision or infibulation. In short, the reasons given to justify the practice can be grouped as follows:

- Controlling women’s sexuality

Removing the most sensitive parts of the external genitalia, and in particular the clitoris, is believed to reduce a woman’s desire for sex and to ensure virginity until marriage and fidelity/chastity in married life. - Upholding cultural tradition and maintaining social cohesion

In the colonial and post-colonial context, initiation rites for girls are thought to play a significant part in maintaining the social and cultural heritage. - Beliefs about hygiene and aesthetics

Removal of the external female genitalia, which are regarded as dirty, ugly or impure, is said to increase hygiene and women’s attractiveness. - Enhancing fertility

These practices are believed to strengthen reproductive health and child survival. - Following religious beliefs

Some Muslim communities practise FGM because its members think it is required by Islam. However, genital mutilation predates Islam and is not mentioned in the Quran. Furthermore, FGM is not confined to Muslim communities, but is also practised by Christians (Catholics, Protestants, Copts) and animists.

Also, it is clear that FGM is a source of income and social recognition for traditional practitioners, which they are reluctant to give up. In some countries, health professionals who perform FGM have turned it into a lucrative business. Currently, the average age of cutting is falling, which indicates that the practice is decreasingly associated with initiation into adulthood and increasingly with a rite of identity. It is done to belong to a particular group, ‘because our mother has been cut, our grandmother too … It’s tradition.’ Social pressure is strong. A young girl or woman who has not been cut is regarded as impure in her community. She is ostracised, and cannot marry or even prepare food for her family. Women who have their daughters mutilated do so with the best of intentions. By respecting the tradition they want to protect their daughters from shame, social exclusion and isolation. Whatever the reasons cited for defending and perpetuating these practices, it cannot be ignored that they are a form of violence against women in contexts that, no matter how different, are always marked by gender inequality. They damage the physical and psychological integrity of individuals and constitute a violation of the rights of women and children.

Circumstances in which FGM takes place

In Senegal, for instance, the mutilation is performed by women belonging to the cast of blacksmiths, elsewhere, by an older woman or traditional midwife. The place of the man in the procedure varies by region. Generally, the man plays no active part and is not present during the procedure. In Egypt or Nigeria, however, the mutilation may be performed by a man (for instance, a barber).

No-one tells the child or adolescent what she will have to endure. Most often, the mutilation is carried out without any form of anesthesia. The girl is immobilised and held. The mutilation may be carried out using a knife, a razor blade, broken glass or some other cutting instrument. Infibulation may take fifteen to twenty minutes, during which the wound is sewn up using rough, unsterilised thread; in Somalia, acacia thorns are used to hold the two sides of the labia majora together. A poultice containing ashes, dirt, eggs, herbs, etc. is applied, which is believed to facilitate healing and prevent infection and haemorrhage. Sometimes, the girl’s legs are bound together until the tissue has bonded, causing the wound to become infected with every urination or defecation.

In some countries, the mutilation is becoming medicalised and practised by health professionals, even in hospital. Such is the case in Egypt, where 77.40% of all excisions on girls between the ages of 0 and 17 are performed by medical personnel, according to the 2008 demographic and health survey. Following the death of an eleven-year-old girl after an excision performed by a doctor in June 2007, a ministerial decree was issued the following month prohibiting excision in public and private medical institutions in Egypt. Infibulation prevents a woman from having sexual intercourse. On the day of marriage, the infibulation scar must be opened with a cutting instrument by an older woman or by the bridegroom. At best, this defibulation is performed in hospital. In other cases, the bride is gradually torn open by the bridegroom. Sometimes, full intercourse is not possible until after many failed attempts. After childbirth, the woman’s vagina is sewn up again. This is called refibulation.

International law and FGM

Female genital mutilation is an inhuman and degrading practice in the sense of several International Conventions, such as the European Convention on Human Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. FGM is considered as a form of persecution in the sense of the Geneva Convention and likely to justify refugee status. Recent developments regarding application of asylum and fundamental rights at European Union level or in the context of the Council of Europe show that these institutions are willing to offer better protection to girls and women at risk of FGM and other harmful traditional practices, such as early or forced marriage. Within the European Union, the Qualification Directive(1) was recently revised to provide better protection of vulnerable groups. Within the Council of Europe, the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, known as the Istanbul Convention(2), was opened for signing, aiming at a better understanding of gender-based violence, whether in the context of the examination of applications for asylum, or in the broader framework of domestic abuse. This Convention has not yet come into force.

A recent resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations on intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations, adopted on 20 December 2012, urged all states to condemn all harmful practices affecting women and girls, and female genital mutilation in particular, and take all measures necessary — including the enforcement of existing legislation, awareness-raising and the allocation of sufficient resources — to protect women and girls from this form of violence.

Belgian law and FGM

With the law of 28 November 2000 regarding the protection of minors under the criminal law (entered into force on 1 April 2001), Belgium incorporated a specific article concerning FGM into the Criminal Code (see box below). To date, no infraction has been reported to the Belgian judicial authorities. However, there is a suspicion that FGM is performed secretly in Belgium and other European countries.

The act is limited exclusively to mutilations inflicted on women, even consenting. The severity of the effect, the pursuit of profit, minority , and, in general, situations of dependency constitute aggravating circumstances. Piercing, tattooing, sex change operations, or acts for medical purposes are excluded. Other provisions of the law on the criminal protection of minors are important for the assessment of its overall economy. Article 458bis of the penal code, which provides relief from the duty of professional secrecy when minors or vulnerable people are concerned, includes cases of genital mutilation.

In Belgium, the protection of girls is also taken into account in the civil area: in case of emergency, the judge may entrust the child to one of the parents and forbid the child from leaving the country, on the obvious condition that there is serious risk of mutilation.

To protect a girl from her own family, the prosecutor may request the juvenile judge to take protective measures (such as removing the child from its family and entrusting it to the care of a third party). This is an extreme measure with heavy consequences: the parents aren’t necessarily ‘bad parents’ and the separation may be as painful as it is difficult to comprehend, for the parents as well as for the child.

FGM and asylum application

The law of 15 December 1980 on access to territory, residence, establishment and expulsion of aliens, modified in 2006, regards physical or psychological violence, including sexual violence, as a form of persecution constituting a valid motive for granting asylum.

In the context of application for asylum and regularisation for humanitarian reasons, the authorities are also sensitive to the risk of mutilation for girls in their country of origin and for the situation of women who have undergone surgery in Belgium and therefore run the risk of reinfibulation. The attitude of the asylum authorities towards FGM is to be understood in the context of their current approach to early and forced marriage.

1 Directive 2011/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 laying down rules concerning the conditions to be fulfilled by third-country nationals or stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, for a uniform status for refugees or persons eligible for subsidiary protection and the content of the protection granted (recast), JO L 337/9 of 20.12.11. ↑ Back

2 Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, Istanbul, 11.V.2011, http://conventions. coe.int/Treaty/EN/Treaties/Html/210.html. ↑ Back